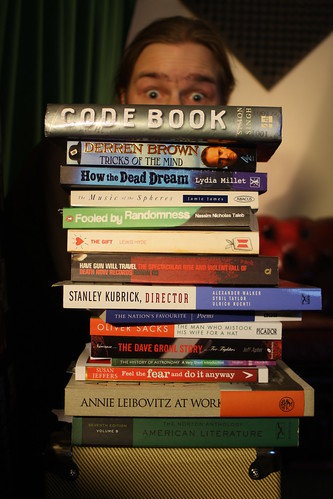

I just finished reading Phantoms in the Brain: Human Nature and the Architecture of the Mind by Ramachandran after coming across a few good quotes from it in Consciousness: A Very Short Introduction. Ramachandran seems to be in the same circles as Oliver Sacks and the book very much reads like a more in-depth version of The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, almost a follow up to it, perhaps with a bit less sensationalism, depending on your take of The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat.

It jumped straight into a full on explanation of phantom limbs and his experience of the whole strange topic. Although I at first felt like this was more than I ever wanted to know about phantom limbs there were some amazingly simple 'cures' for a phantom arm for example, that sounded like they should have been discovered two hundred years ago, yet were from the late 80s. He talked about patients suffering from a phantom lower arm where their hand was permanently stuck in a clenched fist position, so much so that the phantom muscles in their phantom arm ache chronically and the phantom finger-nails in the phantom fingers dig into their phantom palm causing excruciating, incurable pain.

One way he found of relieving this pain was to construct a simple black box with two holes on the front and a removable lid. The patient inserts their two arms, both fists clenched, into the box (one arm is a phantom) then upon removing the lid of the box the patient actually sees two reel fists in the box via a mirror in the middle of the box, reflecting the real arm in the position of the phantom. When ready, the patient un-clenches both fists and for the first time (via their own visual feedback system) is able to feel the relief of the phantom hand relaxing and un-clenching.

This hasn't turned out to be a cure for phantom limbs but more of a hint to their nature and whereabouts in the brain and within the human condition. Ramamchandran lightheartedly mentions how patients have been dispatched with magic black boxes of their own to work with for 20 minutes a day to relieve the discomfort of a phantom limb.

The main reason I wanted to read the book was for its insights into our consciousness and our ideas of self. This was touched on quite a bit in the first chapter in relation to perfectly sane people feeling like they can reach out and pick up an object within arms length, even though they are completely aware of having no arms. There were interesting points raised about our visual feedback system and how easy it is to distort our image of our physical self by closing our eyes and engaging in simple exercises.

The more interesting points were mentioned in what I felt was the best chapter called 'The Unbearable likeness of Being'. It was centred around a case of Capgras' delusion where the patient insisted that his parents were in fact impostors that looked just like them but lacked the particular 'isms' of his real parents. There were extra twists where the patient would accept them as his own parents whilst talking to them over the phone, but not face to face. Through this case and Ramachandra's experiments with the patient all kinds of links between our various sensory input systems were uncovered and illustrated in their use in making sense of the world around us (when not suffering from a neurological disorder).

Throughout the book Ramachandran laid down interesting ideas about how we construct our own reality and how we rely on particular functions to do so (using interesting examples of how we fill in our blind spot because we can't function with holes throughout every scene we look at "it's clear that the mind, like nature, abhors a vacuum and will apparently supply whatever information is required to complete the scene" (p.89)).

Although not as focused on consciousness as I might have liked Phantoms in the Brain is a good read, has given me new ideas and understandings and I will be recommending it to my Oliver Sacks fan friends.

I think my favourite quote from the book is

"Most organisms evolve to become more and more specialized as they take up new environmental niches, be it a longer neck for the giraffe or sonar for the bat. Humans, on the other hand, have evolved an organ, a brain, that gives us the capacity to evade specialization. We can colonize the Arctic without evolving a fur coat over millions of years like the polar bear because can go kill one, take its coat and drape it on ourselves. And then we can give it to our children and grand children." (p.190)

Saturday, 29 October 2011

Phantoms in the Brain

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 comments:

Post a Comment